Are economics degrees fit for purpose?

- 5 February 2016

- Business

Spencer Platt

Spencer Platt

In many universities, something is stirring up the "dismal science", as economics is sometimes derogatorily called.

Students of economics are up in arms about what they are being taught, and how. They are not just protesting - they are doing something about it.

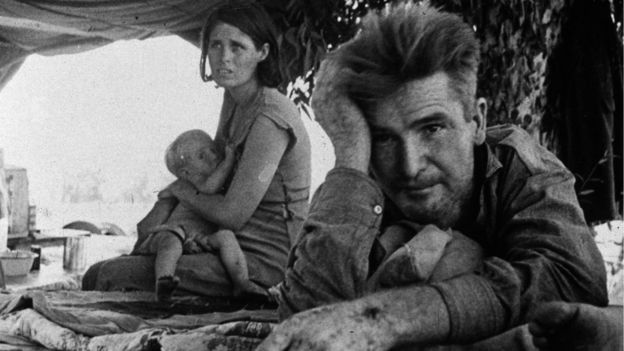

The movement seems to have started in Manchester around 2010. Many university economics departments received a notable increase in applications from would-be undergraduates as a result of the great financial crisis that broke cover in 2008.

They were - say the new students - alarmed by the world they found themselves in. They wanted to find out more about the crisis, and what could be done to prevent another one.

So they signed up for economics. But a year of teaching left them frustrated and surprised.

There was scarcely a mention of the crisis, or of the real world that it so badly jolted. Typical economics undergraduate teaching - they said - concentrated on a model of economics that almost ignored the booms and busts they had experienced as school students.

They further claimed that they were taught by specialists who concentrated on the concept of theoretical economic men or women who took rational, optimal, decisions, when confronted with great big problems, or little ones. Mathematics was often a central part of the economics course.

The odd, unpredictable ways that people behave was ignored. And so were lots of other schools of economic thought.

Getty Images

Getty Images

In particular (and to an economics ignoramus such as me this seems particularly strange), there was little or no reference to the history of economics.

The lessons of the past were taught only in as much as they were reflected in current economic models. It was rather as though the past had not happened, or at least had not made an impact on the way the subject was being taught, or ought to be taught.

Concerned by all this, a few students called a meeting at Manchester University Union, a traditional response. There was not an overwhelming turnout - about five of them. But those five were sufficiently fired up to get something started - something called the Post-Crash Economics Society.

And when they started meeting regularly to hear speakers talking about the things they felt were being ignored in their undergraduate courses, crowds gathered. Not just economics students, but those from other social science disciplines as well.

'Time to rethink?'

The organisers drew early strength from a slightly unlikely source - the Bank of England.

In 2012 the Bank organised a conference under the rousing title "Are Economics Graduates Fit for Purpose?". Were they up to do doing the job that businesses, and government departments, wanted from their newly qualified recruits?

The Society of Business Economists asked a similar question. Employers expressed their doubts about their new economists.

And this chimed with the frustrations of the students themselves. They were - after all - now paying hefty fees to learn stuff that their potential employers were also questioning. The movement gathered momentum.

The post-crash students in Manchester published a well thought out report on what was wrong with the teaching they were getting.

In a foreword, the Bank of England's chief economist Andrew Haldane contributed this battle cry: "It is time to rethink some of the basic building blocks of economics." Striking stuff.

Locally organised, the movement spread to many universities in Britain. And it then linked arms with students in other parts of the world.

In China, the USA, Brazil, India, Italy Turkey, France, Germany and other places, there are now groups gathering under the banner of something called Rethinking Economics.

It describes itself as an international network of people seeking to demystify, diversify, and invigorate economics.

The main concern of the "rethinkers" seem to be the lack of what they call "plurality" in the way the subject is taught. As I said, in recent decades, a single economic school of thought - neo classicism - has come to dominate university teaching.

The academic world is as subject to fashion as are most other walks of life. Despite its sometime aspirations to be a hard science, dominant economic ideas come and go.

Getty Images

Getty Images

For some time this appeared to be implicitly recognised in the way that the Nobel Memorial Prize for Economics was seemingly awarded - one year to a follower of JM Keynes, and then to a market forces supporter inspired by the monetarist views of the late Professor Milton Friedman of Chicago. By caricature, a pendulum swing from left to right and back again.

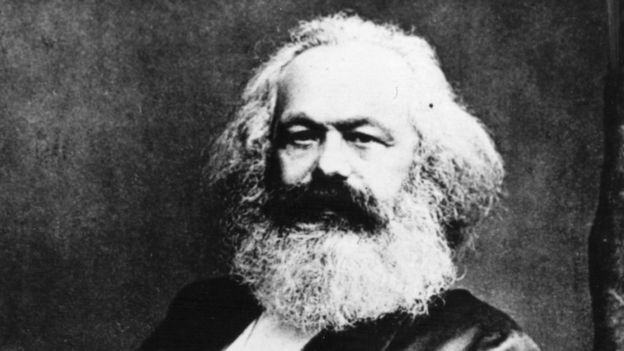

But the idea of pluralism goes wider than caricature. Many students would like to hear about the applicability of other different approaches to economics - about Marxism, Schumpeter, classical, Austrian, Keynesian, behavioral, developmental economics. Some would include something called feminist economics.

In answer to the student challenge, university economics faculties argue that they are changing parts of their approach. Some are readmitting the history of economics into their syllabuses, a very welcome inclusion.

Getty Images

Getty Images

And one or two universities - keen to make a name for themselves - are making what seem to be bigger changes to their teaching. University College London has introduced a new curriculum. Leeds, Greenwich and Kingston Universities have done some large-scale rethinking of their economics teaching.

Meanwhile - unlike many other student initiatives that so quickly run out of steam - the movement appears to be gaining momentum. Coming soon is a very accessible economics website aimed at the general public, not just students. Later this year there's a book on the subject.

It makes you wonder whether the students now working together to Rethink Economics have not evolved a slightly new economic or educational model for themselves, out of sheer frustration.

So stung have they been by what they thought they were not being taught, that they have gone out and organised it for themselves. Diversity by other means, you might say.

And it matters because economic ideas touch all our lives. To make the world better, they ought to be understandable.

Peter Day's Global Business on Educating Economists goes out from Saturday 6 February, at 22:32 GMT on the BBC World Service.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire